Networking in Core

Overview

Core lets you create multiplayer games right away, and provides tools for testing them. These games are hosted on Manticore's servers, which automatically create new instances of the game when players connect.

Core does this automatically which can hide the details of what is happening behind the scenes. This is important, because creating robust, performant games is difficult without an idea of how the networking works and how to configure it.

This document will explain how networking works, explain each of the contexts used in Core, and give examples of when to use them.

How Networking Works In Core

The Game Definition File and Client Side Loading

When a multiplayer Core game starts, a session of the game starts running on the server. Each player that connects to the game first downloads a game definition file This contains everything they need to run the game as a client - the objects that are part of the scene and the client-only effects like music and menus. This is not the full game. The server is the only one that has access to the full game - but the clients do receive enough to run the game with the server's help.

Enter the Server

Once the game starts running, the server is in charge of most of the actual game logic. Most scripts only run on the server, and most things that clients see only happen because the server sent the client a message saying "hey, do this thing!"

Whenever something changes, the server tells all the clients about the change.

Some objects (most notably players and projectiles) have some extra code in them to make them feel more responsive on the client, but the basic model is the same: If a player tries to move, the player's client tells the server, and (assuming the server agrees that the player can move there) the server then notifies all the other clients, "hey, this player has moved!"

Whenever something changes, the server tells all the clients about the change. But the exact actions taken depend on the object that is changing and how it has been declared.

Contexts

Overview

The six main ways objects can be defined are:

- Default Context

- Default Context (Networked)

- Client Context

- Static Context

- Server Context

- Local Context

Default Context

Objects added to the Hierarchy are in placed in the Default Context by default. (Hence the name!) They have not been marked as networked, and so are assumed to never, ever change. Anything that you put in the Hierarchy will start out in the Default Context.

In general, you should try to have as much of your game as possible in the Default Context.

This kind of object has the best performance, because it never changes. The client and the server never need to talk about it. When the client loads the game definition it gets a list of all the static objects, and their sizes, rotations, positions, colors, etc. It puts them in the world, and then never has to think about them again, because it knows they can't change.

Example Uses of Default Context

Things you would usually place in the default context include:

- Level geometry (shapes and objects) that never changes or moves.

- Triggers that are always active

- Looping sounds that play as long as the game is open

Default Context (Networked)

Items in the default context can be marked as (networked), by right clicking them in the Hierarchy and selecting Enable Networking. These are frequently called Networked Objects. All children of networked objects will also need to be networked.

Marking an object as networked tells Core that this object might change during gameplay.

Networked objects can be moved, resized, spawned, and destroyed using a script. Any time a networked object is changed, the server sends an updated version of the object to all clients. The server sends the ENTIRE object. Even if only one property on the object is changed, the entire object is turned into data and sent to all the clients.

Networked objects are the most expensive kind of objects, because the server has to keep track of when they change, and pass that information from the server to the clients when they do, generating network traffic. Because games often have things that move, most games will have many networked objects, but in general, creators should try to keep their total number of networked objects to a minimum, and move as much as possible into Client or Static Contexts.

The Performance window reports how many networked objects a game has at any given time, which can be very useful for diagnosing performance problems. Large numbers of networked objects will cause games to run slowly.

Example Uses of Default Context (Networked)

Things you would usually mark as networked include:

- Objects that move, like moving platforms or doors that open

- Triggers that need to be disabled

- Templates that you want to be able to spawn at runtime

- Enemies that move around and can be destroyed

- Weapons or power-ups that vanish when collected.

- Sound effects that play in specific circumstances

Client Context

A Client Context is a special kind of folder that you can create, by right-clicking in the Hierarchy, and selecting Create Network Context and Client Context.

All children of a client context only exist on a player's local version of the game. The server does not load or synchronize any of them. This brings a number of limitations, but also a few advantages.

The biggest advantage of using the client context is that objects in a client context don't cause any network traffic and doesn't increase the server load at all, because the server doesn't know about anything in a client context. This makes client contexts great for cosmetic effects that don't need to be synched up between players, such as explosions, debris particles, or extremely complicated models.

The other advantage of the client context is that objects can look different to different players. This makes them ideal for setting up things that look different depending on who is looking, like User Interface elements that show individual player data.

Any objects in a client context cannot be collided with by players or targetted so they can also be used to simplify collision calculations. Instead of allowing collision with an intricate object, place it into a client context, and then create an invisible cube (or other simple shape) to handle the actual collision.

Scripts inside of a client context will run on the client side,but can only affect things that are in the client context. So a client context script cannot move an object in the default context, for example, even if that object were networked.

If you need to have a script in a client context affect server logic, use Events.BroadcastToServer(). See the Core API for more information.

Note

Every child of the client context is ignored by the server, but the client context ITSELF is still a normal object that can be referenced by Lua scripts and (if it is marked as networked) moved or manipulated.

Example Uses of Client Context

Things you would usually place in a client context include:

- User interface, menus, HUDs.

- All Visual Effects.

- Templates that you want to be able to spawn at runtime.

- Decorative geometry that doesn't need collision.

- Scripts that control any client-only things.

Server Context

A Server Context is another a special kind of folder that you can create, by right-clicking in the Hierarchy, and selecting Create Network Context and Server Context.

Anything under a server context only exists on the server. It is never sent to the client at all. Normally, all scripts are downloaded by the client, even if they are not run, for compatibility reasons. Any scripts that are placed inside of a server context (and exist nowhere else in the Hierarchy) are not downloaded. This makes server contexts extremely useful to anyone who wants to keep their game logic safe from the prying eyes of players.

Any geometry inside of a server context is automatically non-collidable, so players cannot stand on it or target it.

Example Uses of Server Context

Things you would usually place in a server context include:

- Scripts that you want to prevent players from being able to inspect

- Visual widgets that you use while editing the game, but don't want to include in the published version

Static Context

A Static Context is a third special kind of folder that you can create, by right-clicking in the Hierarchy, and selecting Create Network Context and Static Context.

They share traits with both networked and non-networked objects, and they have a few rules:

- Scripts in a static context run on both the client and the server.

- Scripts can spawn objects into the static context, but after they are spawned, they behave like non-networked default context objects, and cannot be modified or deleted.

- Objects spawned are not sent over the network, so the client and server scripts should make sure to spawn the same objects.

The main use for this context is in creating procedural geometry. If both the server and the client build a level from a common random scene, this becomes an efficient way to make procedural levels that are synchronized between the clients and the server.

Example Uses of Static Context

Things you would usually place in a static context include:

- Procedurally generated geometry that needs to have player collision

- Complicated geometry that needs to be collidable, but only needs to move as a unit.

Local Context

Local Context is very similar to Static Contexts, except that objects within them can be modified. However, any changes made to the objects in the Local Context are made independently by the server and each client, and are not networked automatically. Creators must take care to ensure that client and server state match, or players may experience unexpected behaviors (for example, jittery movement, teleportation).

Local Contexts can be used when creating gameplay objects which have a stationary server component (like a trigger), but an animated client component (like a rotating visual component).

Local Contexts can also be used by advanced creators who want to create synchronized functionality without using networked objects, instead synchronizing by some other mechanism, like having Local Context scripts perform changes based on a dynamic custom property on a networked object. Creators can use this to potentially improve performance and functionality for games that have higher player counts.

Nested Contexts

Nested Contexts allow creators to include contexts inside a different (non-default) context. For most cases, the first context is respected. For example, if a server context is a child of a client context, then the server context will be treated as a client context.

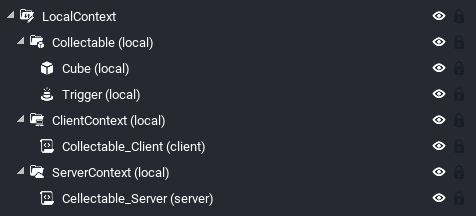

There are two specific situations when the nested context is respected. The first instance is a server or client context inside a static context. The second instance is a server or client context inside a local context. One example where this can be useful is to make a collectable, non-networked object. Using nested client and server scripts inside the local context for a collectible allows creators to spawn local effects and handle server collision.